I pray the Lord my soul to keep.

If I should die before I wake,

I pray the Lord my soul to take.

God Bless Mummy, Daddy,…..

When I was young, I used to say this prayer every night in my bed. Thanks to Catholic schooling, I was convinced that I would die before I woke and I wanted to be sure and use my heavenly power to bless the dearest people in my life. I would ramble right through my immediate family, assuming God knew that much. Then I would branch out into the family tree: my aunts and uncles, my cousins, my grandparents.  Evidence (http://www.geni.com/tree/index/619036) suggests that getting through those generations was no small feat. Once I was done with the living, in a half-slumber, I would imagine my deceased grandfather and two uncles sitting at a table, in the cloud-filled heavens. Quite literally, I would be looking right up at them as if from underneath the cloud on which they were perched. I imagined them in uniform: my grandfather in a fireman’s outfit, my uncle in his army fatigues, and my other uncle in a t-shirt and bell-bottom jeans. They appeared at the table at the respective ages of their deaths: 44, 18, and 15. It strikes me that I thought of them each night (always in uniform, always playing cards), but their deaths had an impact on my father and I was aware of that impact at a very young age.

Evidence (http://www.geni.com/tree/index/619036) suggests that getting through those generations was no small feat. Once I was done with the living, in a half-slumber, I would imagine my deceased grandfather and two uncles sitting at a table, in the cloud-filled heavens. Quite literally, I would be looking right up at them as if from underneath the cloud on which they were perched. I imagined them in uniform: my grandfather in a fireman’s outfit, my uncle in his army fatigues, and my other uncle in a t-shirt and bell-bottom jeans. They appeared at the table at the respective ages of their deaths: 44, 18, and 15. It strikes me that I thought of them each night (always in uniform, always playing cards), but their deaths had an impact on my father and I was aware of that impact at a very young age.

During the holidays when we would visit my grandmother’s house, after a long night of festivities, inevitably I would find myself daydreaming at the hallway desk which sits right by the front door.  Sitting on my mother’s lap in the living room, listening to her voice through her chest engage in that boring adult conversation, I would suck my thumb and stare through the doorway at the desk. The desk was pristine; I would venture to say that it was dusted each day. Atop it were two framed photos: one of my uncle George and one of my uncle Tommy. The photos were black and white and displayed clean-cut, happy teenagers. I would listen to the grown-up conversations while I stared at the photos and think about how those boys were the brothers of people in that very room. It was strange to me that my relatives did not talk about George and Tommy, their banishment to the hallway desk seemed eerie and strange to me. My uncles seemed so young and vibrant and I craved to meet them, to hear more about them, but stories did not come until much later in my teens, when my dad began talking about them and

Sitting on my mother’s lap in the living room, listening to her voice through her chest engage in that boring adult conversation, I would suck my thumb and stare through the doorway at the desk. The desk was pristine; I would venture to say that it was dusted each day. Atop it were two framed photos: one of my uncle George and one of my uncle Tommy. The photos were black and white and displayed clean-cut, happy teenagers. I would listen to the grown-up conversations while I stared at the photos and think about how those boys were the brothers of people in that very room. It was strange to me that my relatives did not talk about George and Tommy, their banishment to the hallway desk seemed eerie and strange to me. My uncles seemed so young and vibrant and I craved to meet them, to hear more about them, but stories did not come until much later in my teens, when my dad began talking about them and

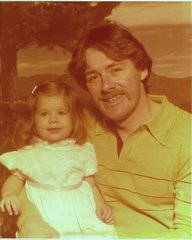

My uncle George was born on January 27, 1948 and my father was born on January 9, 1949. They were Irish twins, born within a year of each other. From stories and photos, I gather that they were best friends…or at least my father’s best friend was George. In the 1980s, one of my fellow ballet student’s mother realized that I was George’s niece and that Freddy was my father. She talked about how George was a bit more extroverted and Freddy seemed to genuinely look up to him. This outside validation of a non-family member mentioning (and remembering fondly) George was momentous for me because he had started to become three-dimensional. Before that moment, I had only known that he was my dad’s big brother who was killed in

In 1968, George was killed in

In 1968, George was killed in

When I was little, the extent of my father’s  He said it was tranquil and the jungle was lit by the moon and that you could see a cigarette burning at the end of someone’s mouth from a mile away. Now that I am older, and he is too, I hear more stories about his time there and am shocked that 37 years later he is just beginning to locate fellow soldiers from his platoon. I would have needed them immediately upon return.

He said it was tranquil and the jungle was lit by the moon and that you could see a cigarette burning at the end of someone’s mouth from a mile away. Now that I am older, and he is too, I hear more stories about his time there and am shocked that 37 years later he is just beginning to locate fellow soldiers from his platoon. I would have needed them immediately upon return.

I suppose his exceptional return to the

He flew from Saigon to

Once at

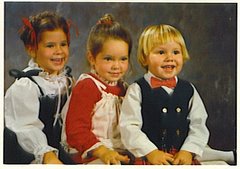

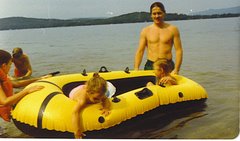

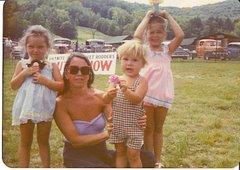

The next few years are not yet clear to me and they are probably not very clear to him. I do know that he and my mother attended war protests. Photos are evidence of long hair, mustache, occasional partying, and fishing in the

The next few years are not yet clear to me and they are probably not very clear to him. I do know that he and my mother attended war protests. Photos are evidence of long hair, mustache, occasional partying, and fishing in the

In the early morning hours one night during the summer, the phone rang at the family home in Roslindale. Tommy left a party and had been driving at 15, underage and without a license, in

I had a blast of panic last winter when my dad called me on my cell phone at 7:30 in the morning. I ignored the first call, as I assumed it was my mom wanting to say something like “good morning”, but after the back-to-back calls decided I should pick up. On the other end was my dad telling me, in his voice that he uses to talk about the Bruins, “Danny’s been in a car accident. He broke his back. We think he’s okay. He went through the sunroof on 93 North. I need to get in touch with Kirsten because Danny was working on something for her.” It was just another crisis drill for my dad, who seemed most concerned about a reservation confirmation for my sister’s business, but it was whole new territory for me. Chris and I had recently been watching the series Big Love and I think its opening sequence influenced my imagination. Immediately, I saw our family as a circle, holding hands and I saw Danny letting go and dropping out of the formation. It was frightening to me that we would have to re-shape into something else and I could feel each of us reaching toward him, urging him to come back. I thought about my dad’s family and how many times their circle has had to take new shape, how some of them still are urging George, George, and Tommy to come back.

Needless to say, Danny is fine. He’s better than probably anyone who has had his injury. On the bus ride up to

3 comments:

This is a very moving post, Erin. It brings back the phone calls from hospitals that I have received. But I think it's better to think about it every now and then than to completely block it out.

Erin, I commend you for bringing them back to us so vividly. Lest they not be forgotten. Thank you for being such an excellent communicator...it brings everyone so much closer even tho through tears. Bless you. Auntie Gail

I have seen this story written many times in the school careers of all you children- at St. Pat's, BB&N, Pingree, KUA and probably into your college writing courses, but I can't say that I have seen such a poignant, mature version as this one.

It never fails to bring tears and the understanding that the Gottwalds are the way they are because of these events -- because they have been re-shaped far too many times.

But for the grace of God.

Love,

Mom

Post a Comment