Thump, thump, thumpity, thump…there are flashes of a nursery rhyme going through my head as my stare jumps intermittently among the six legs.

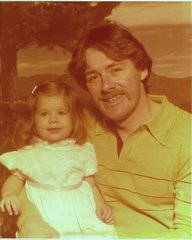

I am trying to hypothesize why men twitch their legs so much when they sit at a table. I don’t remember my dad ever doing this, but maybe his nail-biting is a substitute. I glance over at the women in the shop and they are calmly typing on their keyboards: one woman has her shoes off and is sitting criss-cross applesauce (I teach too much) in her seat while the other woman has her feet twisted around the legs of the chair where they meet the floor.

The women are all wrapped up and the men are flailing.

A cell phone rings and a woman answers with a barely audible “hello.” She’s trying to keep her voice down. This is very polite. As if this call is a signal to make his own phone call, one of the thumpers digs in his bag for his cell phone and then announces “HEY, JEREMY. WHAT’S UP.” This is not very polite. All the women in the room agree on this via eye contact. All the men in the room seem oblivious.

Thump, thump, thumpity, thump.

The woman whispers into her phone and the man uses a voice I imagine he uses at an overcrowded bar to talk to Jeremy.

I put on my headphones.

Fast forward twenty minutes later and there is a gap between my Kings of Convenience tracks and I hear the music that is playing over the coffee shop’s sound system. It’s music that brings such a visceral reaction that I consider packing up to leave. I’m almost done with my coffee, anyway. Instead, though, I take off my headphones and listen and write down some of the lyrics:

Seeing you

Or seeing anything as much as I do you

I take for granted that you're always there

I take for granted that you just don't care

Sometimes I can't help seeing all the way through

It's important to me

That you know you are free

Cuz I never want to make you change for me (falsetto)

I don’t know who sings this song. I don’t know if it’s a good song. But I hate it.

It reminds me of the long summer drives to

Thump, thump, thumpity, thump…

During my pubescent summers in

When I was about 8 years old, my aunt Gail pulled up to the trailer in her car. She lived in a real house in

At twelve years old, I felt like a veteran. I knew that bad things could happen. I preferred not to hear about my best friend dying via an obituary in the newspaper but I liked to think that I was prepared for that possibility.

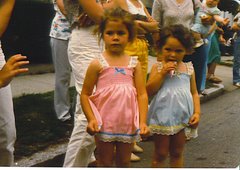

On summer evenings like this (held hostage at the trailer park), I would physically situate myself between the children and the adults.  My sisters, brothers, cousins, neighbors, and family friends would inhabit the dirt roads. Their numbers made the 10 mph traffic come to complete stops and sometimes resulted in Cadillacs off-roading as to not disturb the congregating children. Unimpressed by their simpleton ways (literally playing with dirt, playing catch with a baseball, exuding such excitement over trivial things like the dollar with which they were going “to buy fifty goldfish” candies at the front store), I would stare and bite my nails while listening to the adult conversations. Sitting in the big indoor porch area that housed four pullout couches to accommodate my ever-expanding family, I had a bird’s eye view of the dirt-goers. This positioning also allowed me to overhear bits of grown up conversation that I probably wasn’t “supposed” to hear. But since I wasn’t slightly interested in the subject matter, they were like background noise that never fully tuned in.

My sisters, brothers, cousins, neighbors, and family friends would inhabit the dirt roads. Their numbers made the 10 mph traffic come to complete stops and sometimes resulted in Cadillacs off-roading as to not disturb the congregating children. Unimpressed by their simpleton ways (literally playing with dirt, playing catch with a baseball, exuding such excitement over trivial things like the dollar with which they were going “to buy fifty goldfish” candies at the front store), I would stare and bite my nails while listening to the adult conversations. Sitting in the big indoor porch area that housed four pullout couches to accommodate my ever-expanding family, I had a bird’s eye view of the dirt-goers. This positioning also allowed me to overhear bits of grown up conversation that I probably wasn’t “supposed” to hear. But since I wasn’t slightly interested in the subject matter, they were like background noise that never fully tuned in.

The problem was that there was no structure.

And I was twelve.

When I was ten, I begged my parents for chores and a chalkboard that we could place in the kitchen on which we could rotate household responsibilities. I wanted to have an allowance and attempted bribing Kirsten and Tommy to join my cause. They found me uninspiring and my protestations went completely unsatisfied by both my parents and my siblings. Early on, I felt like I was different. They seemed content with the way things were. Now that I was twelve, I decided that if I couldn’t influence the management of my house the least I could do was be the boss of my own world: my room. I tore through magazines, ripping out ads that I thought were cooler than my wallpaper: Anna Nicole Smith’s early Guess Ads, pictures of Kirk Cameron & Leonardo DiCaprio (Growing Pains), Chad Allen (Our House), and Sinead O’Connor (Nothing Compares 2 U). With scotch tape in hand, I plastered these magazine pages all over my pink flowered walls. I also banned entry to all four siblings. Danny and Gretchen, ages 3 and 5 respectively, would come to my door and ask if they could some in and sleep with me (or whatever other requested maternal need) and I would clearly state “no.” Kirsten, aged 10, quickly became the nurturing sister. One day Tommy, aged 9, began stuffing notes through the hole in my door and I quietly creeped up to it, timing his approach, and then abruptly thrust the door open right into his face. As he stood there crying with a growing egg on his head, I yelled at him. I was a hormonal wreck and he should have known that. Although my private den didn’t work out so well for my siblings, it helped me cope with living in a house filled with people that I felt God had mistakenly assigned me to. It must have been around then that I “lost” my

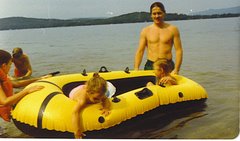

One summer night at the trailer, I was laying amidst three other small bodies (not enough sleeping areas this night…it must have been the 4th of July) on the pullout couch in the living room (pull-out couch #5). It was the middle of the night and I wasn’t sleeping. It could have been someone snoring, it could have been someone flushing the toilet, it could have been a leaking diaper pressed against my back, it could have been the heat. But I think it was my uncle Eddie. He was out on the indoor porch, pinning up a piece of fabric over one of the windows that looked out onto the dirt road. I think my uncle Dickie was directing him, “to your right…yep, that’s good.” What they were finagling was not a mystery to me. It happened many times, but it struck me that night.

The entire park has about 300 summer trailers and there are about 10 street lights. Mostly, it’s a dimly lit, cozy place... mostly. Outside the Gottwald trailer, however, the brightest streetlight in  Whenever indoor porch sleeping was required at the trailer (summer weekend family overnight attendance), there was 2:00AM whispered bickering as the men would try and figure out how to block out the blinding light. The problem was that a sheet was not thick enough to diffuse the light and a towel was too heavy to hang over the window. At least, I think that was the problem. I know there was a problem, because it never quite worked out for the guys.

Whenever indoor porch sleeping was required at the trailer (summer weekend family overnight attendance), there was 2:00AM whispered bickering as the men would try and figure out how to block out the blinding light. The problem was that a sheet was not thick enough to diffuse the light and a towel was too heavy to hang over the window. At least, I think that was the problem. I know there was a problem, because it never quite worked out for the guys.

The night that Dickie was directing Eddie, it dawned on me that someone should hang blinds. And this thought led me down a dangerous road of worrisome thoughts and anxious confusion: Why doesn’t someone just put up some blinds? Why hasn’t anyone thought of this before? Why am I smarter than everyone else? Why am I sleeping with Danny’s wet diapered bottom pressed into my back? Why are the remote controls to the TV at home taped to 6-inch segments of a hockey stick?

As far as I know, blinds never made it to the trailer. About four years ago, my grandmother sold it after spending fifty summers there. The streetlight drove her (and her sons) out.

About five years ago, Chris and I went to see “Angela’s Ashes” at the movie theater. In the film, there is a puddle that lives outside the

I remember my summers at the trailer park with great trepidation for no apparent reason other than my inability to relax in, what I thought, was an unstructured environment. Of course there was a hidden structure of which I was unaware: showers and baths schedules for 15 people with use of one bathroom, intricate parking configurations so that family vehicles could pull out early without being blocked by the cars owned by my single aunts and uncles, compressed communal grocery shopping lists as to avoid redundancies, laundry rotations of dirt-laden, food-stained clothes. But it all seemed like mayhem to me at the time.

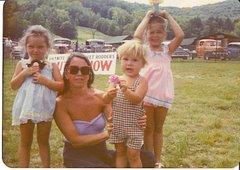

There were efforts to sideline what my mom now refers to my “anxiety attacks”: playing cards, going to arts & crafts fairs, attending a community orchestra performance. Each of these activities helped distract me, but to this day I flinch when someone asks me to play cards and I think twice about going to see community productions. In these situations, like at the coffee shop today listening to that anxiety-provoking music, my worry washes over me briefly.

3 comments:

All right, I understand you are writing your memories, but let me correct them for you!

So readers will realize that your mother did not shrug off the death of her very dearest and closest friend, I feel I must present things in a different light. Of course I felt terrible about Diane's death - she had a two-year old and three-year old. Daddy was not in NH (he was working) when she died of an aneurysm.

When Gail came in, visibly distraught, her words to me were, "I have bad news." My first inclination was that Daddy had been killed while on duty, my knees buckled and I could feel myself losing control (not a good feeling for a control freak). When she told me Diane had died, it was horrible. Maybe you did not want to see your mother upset so you made sure I could go on. But, for me and you little ones, the personal loss we would have had had it been Daddy would have changed our lives on a more magnificent scale, so Diane's death, although horrible, and I miss her every day in my little thoughts, did not affect my ability to take care of you.

While I have the chance (maybe I should start my own blog), the times I thought of Diane most were the times I was having a hard time coping with bringing up children in a crazy competitive world, which had incorporated itself into my peaceful existence at 106 Elm Street when Daughter No. 1, Daughter No 2 and Son No. 1 had leisurely days with structure and planned meals. Then society entered, school started, dance classes began, hockey started and that was that.

I used to say to Diane - I'm not good at this. And then I would think how fortunate I was that I had all of you and your experiences to look forward to, while Diane left this world when her two were babies.

That was my comment above. Not anonymous.

Mom

Daddy and Uncle Eddie may or may not have painted a street light bulb on Bobby's way with a 37 foot long roller and black paint in the summer of 2006 so they could see the stars when they sat out at the campfire.

Post a Comment